In March 2018, Lukpan Akhmedyarov, journalist and activist from Kazakhstan, visited Washington, D.C. to attend a Prove They Are Alive! campaign event and share his experience of being an activist and writer in a country where freedom of speech and expression are suppressed. We asked Lukpan about the realities of environmental activism in Kazakhstan, about some of the challenges which Berezovka residents have faced after their resettlement, and also about love, fear, and standing up for one’s rights.

In March 2018, Lukpan Akhmedyarov, journalist and activist from Kazakhstan, visited Washington, D.C. to attend a Prove They Are Alive! campaign event and share his experience of being an activist and writer in a country where freedom of speech and expression are suppressed. We asked Lukpan about the realities of environmental activism in Kazakhstan, about some of the challenges which Berezovka residents have faced after their resettlement, and also about love, fear, and standing up for one’s rights.

Chief editor of the independent newspaper, Uralskaya Nedelya, journalist and activist Lukpan Akhmedyarov has been covering Berezovka’s environmental and social problems for years, always providing high-quality, impartial reporting. Because of his activities, Lukpan has been subjected to numerous threats to his life and health and was held in a detention center on several occasions. He survived an attempt on his life, and has continuously faced obstacles to his work. In 2012, Lukpan Akhmedyarov won the Peter Mackler Award for Courageous and Ethical Journalism presented by Reporters Without Borders to journalists from countries whose governments suppress freedom of the media.

We are proud that in 2017 Lukpan Akhmedyarov joined the Crude Accountability Board of Directors. His knowledge, courageous ideas, and in-depth understanding of his region’s problems will undoubtedly contribute to our organization’s cause. Below are excerpts from an interview with Lukpan.

On Costs and Rights

When I join a street protest in Kazakhstan, I am very well aware that it will cost me either money, if they impose a fine, or personal comfort, if they hold me for two weeks in jail—not the most comfortable of places.

But I also understand that we all need to go out and protest and pay this price anyway, because by waiting to address problems or covering them up we leave this legacy for future generations to deal with. Social and political challenges have a treacherous aspect: when we put them on hold instead of addressing them the costs do not fade away but increase from year to year.

Berezovka is a typical example of how the government and society should not wait too long to deal with problems. If they had addressed the matter early enough, then, trust me, we would not have had to pay the price of having 28 children urgently hospitalized and then finding out from a health check-up that the rest of the local children also had health problems—not a single one of them was entirely healthy. The price we are now forced to pay is having sick offspring; we have paid with our children’s health.

Back in 2014, when the tragedy occurred, people in Berezovka stopped having illusions: they realized that they could no longer wait for the government and the KPO consortium to live up to their promises and that they needed to act then and there.

Until 2012, the environment had not been a sore subject for the authorities, but today, environmental activism is clearly a big scare for them. But why? Because the authorities can see that environmental problems can trigger social discontent and protest. It turns out that environmental problems, among others, can cause people to go out into the streets and voice their demands.

On the Active Minority

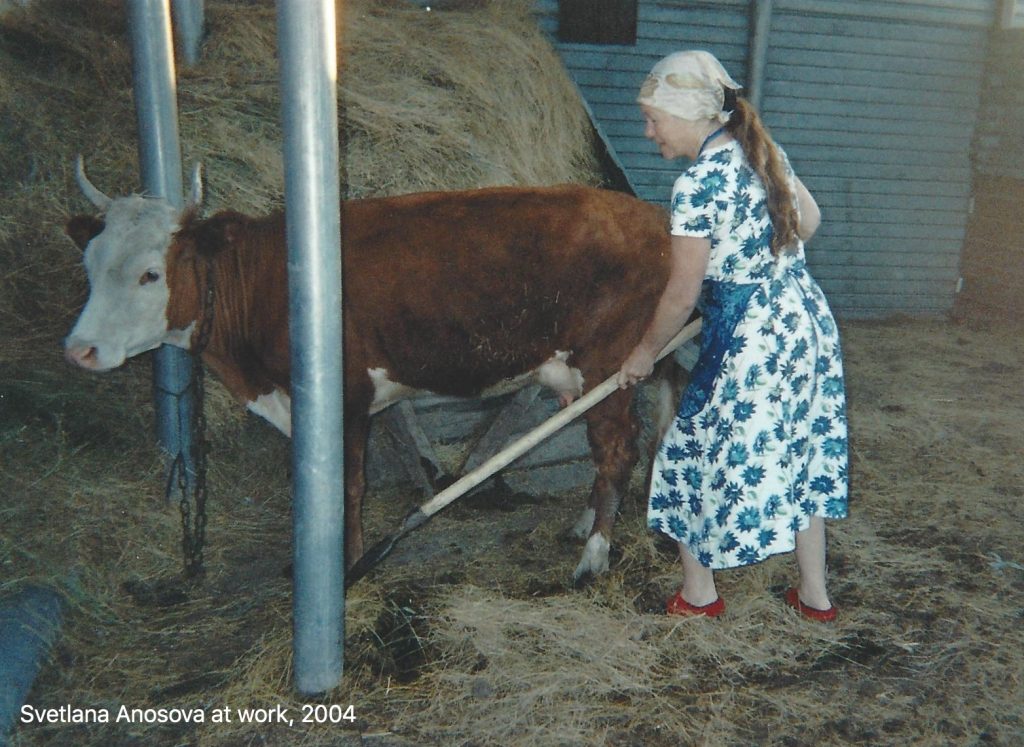

It’s my firm belief that positive and progressive changes in society have always been pushed by a minority. In Berezovka, it was certainly an active minority at the beginning. Svetlana Anosova started on her own, and then her colleagues joined in. These 10 to 20 people have been the driving force all along.

I remember that at first, even fellow villagers viewed Svetlana Anosova with great skepticism. Later, when Crude Accountability came along and started helping Svetlana and Berezovka residents with expert assessments, appeal writing and tracking, and complaint filing, some people rumored that Svetlana was not altruistic but was doing it for money. This was nothing but narrow-minded rhetoric designed to impress idiots, but nonetheless it was extensively used. However, once people could see things changing, their attitudes also began to change.

Standing up for your rights is not a sprint or a short-term race, but a marathon, a long-distance obstacle run. One needs enough patience and energy to endure this road. Svetlana Anosova is a typical marathon runner. She has led this activity for 15 years, without anyone promising or guaranteeing anything to her, without any inspiring examples in front of her but an enormous amount of challenges. She has faced two main opponents: the government and KPO, both huge and powerful with money, influence, and control of the mass media, versus just her, Svetlana Anosova, on her own. And yet, she walked her marathon walk and eventually got the village relocated.

On Love and Fear

When people start their marathon race towards their rights, where they come from is crucial.

I have noticed that when one’s choices and actions are driven by fear, the outcomes can be really bad.

Take, for example, the situation in the U.S. where some people share Trump’s rhetoric against immigrants. Where do they come from? They come from a place of fear that some people will come along and steal their jobs, etc. This usually results in more borders and walls raised between people in a society. Those pushing for tighter immigration control did not expect this result, but it happened because fear was behind their actions.

But there is also another way, when people do things out of love. Love has been at the heart of every successful civic action—love for oneself, one’s children, one’s home and one’s country. Love brings along other things which are essential for positive change: trust and tolerance of others’ opinions.

When I first visited Svetlana Anosova as a reporter to learn more about her, I asked her:

– Why are you doing this? You are on your own. Most other people in the village do not care what may happen. Plus, KPO and the authorities are against you.

– Because I love this village.

And here is the result: she has brought about changes and achieved her goal.

On Social Capital

I like the interview once given by my compatriot Ainura Absemetova who is currently working in Mali at the invitation of the U.N. In one of her interviews, she speaks about social capital. Social capital means that people are willing to trust and support one another.

A society with high social capital is one in which, for example, Lena opens a store in my neighborhood and I go to her store and buy something just to support Lena even though she is not even an acquaintance of mine. In contrast, a society with low social capital is one where the opposite is true, and if Lena opens a store in my neighborhood, I sit there and think, “Just look at her, she’s getting too rich! I am not going to her store.”

To stand up for its rights, a society, in addition to love, must also build social capital and a certain level of active trust and tolerance for one another. Active trust means that we act to support others. Take, for example, the situation in Charlottesville this summer, where people came out to protect the rights of African Americans. The people who came out were not necessarily African Americans and could have stayed at home but they came out to protest against neo-Nazi rhetoric. More recently, after a terrible tragedy—the school shooting—thousand of people across the country have demanded limiting access to firearms.

Social capital in Kazakhstan is critically low, and mutual distrust is high.

We should give credit to Svetlana Anosova and her team who worked for the first seven years without any support from other villagers. Few people have this kind of ability to self-sacrifice. But their commitment produced results, since at some point, social capital increased dramatically in Berezovka. People began to trust one another and they developed an understanding that without joining forces, there was little they could do. The main thing and the greatest achievement in Berezovka has been this growth in social capital. The relocation came as its consequence.

On Activism

I have realized that activism in Kazakhstan is perhaps the only peaceful way, other than journalism, to change anything.

I remember one of my first protest actions. At that time, the president of Kazakhstan was declared “leader of the nation” and a law was adopted to make him president for life. It was in winter, and there was a feeling that everything was frozen, like in a snowy kingdom, not only outside but also inside. And the people were frozen numb and accepted the news as if it were the way it should be. So I thought, nope, I must to do something to demonstrate that far from everyone agreed, that I personally did not agree and had something to say.

This is also an opportunity for me to come clean before myself, a form of moral hygiene at a time when the government tries to smear you as a citizen with its filth, so it may tell everyone, you see, people support us in this. But no, I shall not accept this filth, I shall not live by the rules they are trying to impose, I have my own rules that I live by.

I really like the words which my colleague, journalist Sergei Duvanov, once wrote in an op-ed, saying that we’d had those elections—rather, pseudo-elections—bringing those scoundrels and villains to power. Those scoundrels and villains will now write the laws by which we will live and our children will live. In the future, someone of the new generation will probably ask us, why did you just sit back and watch all this? Therefore I go out to protest, so that in the future I may have the moral right to say: no, I did not just sit back and watch but I resisted the best I could.

I can understand that there is no justice. Erich Maria Remarque once said that there is no justice but mercy and compassion. When I see law and order trampled upon for the sake of a small bunch of people I feel the need to go out and say that I am against it.