July 29, 2025

By Dr. Gubad Ibadoghlu, Visiting Senior Fellow at London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE)

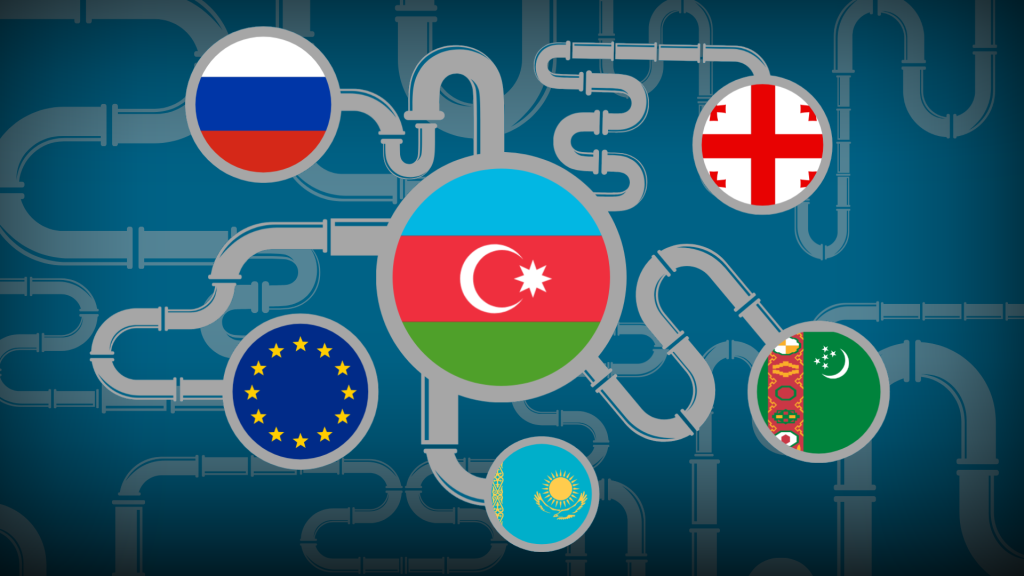

Since 2021, Azerbaijan has been exporting natural gas to European countries via the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), following the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic Partnership in the Field of Energy between the European Union (EU) and Azerbaijan in July 2022, which marked a pivotal moment in the EU’s strategy to diversify away from Russian energy dependence. However, while this move is strategically significant, it raises critical concerns about the EU’s broader energy transition objectives. It highlights a potential contradiction in the EU’s partnership with Azerbaijan, casting doubt on the initiative’s long-term feasibility and sustainability. It also raises questions about the possible reintroduction of Russian gas into the European market under the Azerbaijani brand.

The Gap between Promise and Reality in Azerbaijan’s Gas Exports

After signing the Memorandum of Understanding, it was immediately clear to both Brussels and Baku that Azerbaijan lacked sufficient domestic natural gas reserves to fully meet its export commitments. Following the signing of a memorandum of understanding (MeMo) on the energy field between the European Commission and the Azerbaijani government in July 2022, Azerbaijan is committed to increasing its gas exports to Europe to 20 billion cubic meters (bcm) annually by 2027 — despite widely acknowledged limitations in both production capacity and transport infrastructure.

To meet this target, Azerbaijan must not only ramp up domestic gas production but also expand the infrastructure of the US$ 33 billion Southern Gas Corridor (SGC), which includes three major transit pipelines transporting Caspian gas to European markets. This scale of infrastructure development requires significant capital investment and time — neither of which are guaranteed under the current memorandum. Financing such expansion depends on long-term, binding purchase agreements rather than diplomatic declarations of intent.1 On June 10, 2025, SEFE (Securing Energy for Europe, Germany) and SOCAR signed a long-term natural gas supply agreement, securing approximately 1.5 billion cubic meters annually for the next 10 years, but this is far from the stated goal.

Crucially, Europe’s own energy trajectory calls into question whether Azerbaijani pipeline gas will be needed over the next decade, despite Azerbaijan’s pledge to increase exports to Europe. The EU’s accelerated push towards renewable energy, enhanced energy efficiency, and increased LNG imports suggests a declining role for new pipeline-based gas supply. The European Commission’s roadmap for a 90% emissions reduction by 2040 forecasts gas demand to fall to approximately 117 bcm annually — a 66% drop from 2023 levels.2 This projection diminishes the attractiveness of long-term fossil fuel infrastructure investments, particularly between the EU and peripheral suppliers such as Azerbaijan.

Key Gas Suppliers to Europe

In 2024, Norway and the United States emerged as the primary suppliers of natural gas to the EU, with Norway accounting for 45.6% of pipeline gas and the US providing 45.3% of LNG imports. Other contributors included Algeria (19.3%), Russia (16.6%), the UK (8%), with Azerbaijan accounting for approximately 7.2% of the EU’s pipeline gas imports in 2024, with total exports reaching around 12.6 bcm – a slight increase from 11.8 bcm in 2023, 11.4 bcm in 2022 and 8.2 bcm in 2021. According to Bruegel’s daily import tracker, last updated April 11, 2025, the EU is still receiving slightly more gas from Russia per day than it is from Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijani natural gas was delivered to Europe primarily via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP), which transports Azerbaijani gas through Greece and Albania to southern Italy. In recent years, Azerbaijan has made significant strides in expanding the reach of its gas exports to Southern and Central European countries and the Balkan states and has expanded its natural gas exports via interconnectors to 10 European countries: Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, Slovakia, and North Macedonia. In 2024, the volume of gas exported from Azerbaijan to Italy, Bulgaria, and Greece amounted to 12.6 bcm, which is 97.6% of the gas transported to Europe. These data suggest that, despite political statements, Azerbaijan does not actually export gas to 10 European countries. Instead, it signs agreements with them for this purpose.

In November 2023, Serbia and Azerbaijan signed an agreement for the annual supply of up to 400 million cubic meters (mcm) of Azerbaijani natural gas from 2024 through 2026. Deliveries began later that year, marking a milestone: for the first time, Serbia could partially diversify away from Russian gas during the critical winter heating season.

Despite the contract’s provision for 400 mcm, actual deliveries in 2024 amounted to just 72.1 mcm — well below expectations. Given that Serbia’s annual gas consumption exceeds 3 bcm, the shortfall is significant.

Since then, the partnership has faced major setbacks. On January 11, 2025, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, quoted by the Tanjug news agency, announced that gas supplies from Azerbaijan had been suspended, with no indication of when — or if — they might resume.

In response, Serbia has been forced to reassess its energy strategy. Dušan Bajatović, General Director of the state-owned utility Srbijagas, confirmed the disruption in an interview with TV Prva: “We have essentially negotiated a contract with the Russians, but it will not be signed before September 20, 2025, because at this moment we do not know what Azerbaijan can offer us. There is no gas in Azerbaijan.”

Bajatović’s remarks point to a broader concern: Azerbaijan’s export capacity appears insufficient to meet even modest contractual obligations. This raises serious questions about Baku’s reliability as a long-term energy supplier to Europe.

Notably, Serbia has become the first European country to publicly acknowledge that Azerbaijan currently lacks the gas volumes needed to meet its growing export commitments—a troubling signal for other European partners looking to diversify away from Russian energy.

Additionally, Azerbaijan has gas supply contracts with Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Slovenia and Croatia, a short-term contract with Slovakia and a memorandum with North Macedonia. It has long-term contracts with a fixed supply volume with Italy, Greece and Bulgaria, and contracts without fixed volumes with the rest.

According to the Memorandum of Understanding (MeMo) signed between SOCAR and the Syrian government in Baku on July 12, 2025, natural gas from Azerbaijan will be delivered to Syria via the Kilis pipeline via Türkiye. On the Turkish side, the gas pipeline was extended from Kilis to the Syrian border. On the Syrian side, the technical connections of the pipeline have also been completed. Botas, together with SOCAR, is conducting final tests and checks before the launch of natural gas supply scheduled for August 1, 2025. In the initial phase, 1.2 billion cubic meters will be allocated for electricity generation in the Syrian provinces of Aleppo and Homs. It is worth noting that the implementation of this agreement further constrains Azerbaijan’s already limited capacity to expand natural gas exports to Europe.

Azerbaijan Boosts Supply, but Profits Fall as Europe Looks Elsewhere

Azerbaijan’s export earnings from natural gas surged from US$ 5.56 billion in 2021 to US$ 14.99 billion in 2022, reflecting a sharp increase driven by higher global energy prices. However, Azerbaijan’s export earnings from natural gas declined from US$ 13.68 billion in 2023 to US$ 8.41 billion in 2024. Although Azerbaijan’s natural gas export volumes have increased and its export geography has expanded in recent years, export earnings have declined — mainly due to the stabilization of global gas prices following the previous year’s energy market volatility.

TAP’s current capacity remains a key bottleneck to further increases in Azerbaijani gas exports. However, expansion plans aim to raise its annual throughput to 14 bcm by 2026. Supporting Azerbaijan’s strategy to boost exports to the European market, an agreement between Türkiye’s BOTAŞ and SOCAR facilitates the flow of Azerbaijani gas to Europe via the Türkiye–Bulgaria interconnector, which already transports up to 600 million cubic meters annually. If this upgrade proceeds on schedule and if the Türkiye–Bulgaria interconnector’s transmission is increased from 600 million to 1-2 bcm annually, Azerbaijan could realistically supply between 15–16 bcm of gas to Europe by 2026. Moreover, Azerbaijani gas sold to Türkiye could be re-exported to Europe via Bulgaria, potentially masking the true origin of the fuel.

The EU’s future energy system may have limited space for existing pipeline gas flows from Azerbaijan, especially given the growing role of more flexible and geopolitically aligned LNG supplies. In this context, the EU’s embrace of Azerbaijan as a strategic gas partner may reflect more short-term geopolitical calculus than long-term energy strategy. Some EU experts are already taking a hard look at the union’s gas import needs and are concluding that Baku’s gas is not such a vital element for Europe’s energy future. A report published by the Germany-based Heinrich Böll Foundation, stated, “Azerbaijan is an important but by no means an indispensable energy supplier for Europe.”

Russian Imports to Azerbaijan and EU Commitments

In a geopolitical landscape reshaped by the war in Ukraine and the EU’s subsequent pivot away from Russian energy, Azerbaijan has emerged as a seemingly reliable alternative supplier of natural gas to Europe. However, beneath the surface of this strategic alignment lies a complex and politically sensitive reality: Baku continues to import Russian gas, effectively preserving energy ties with Moscow despite EU sanctions aimed at curbing Russian fossil fuel influence.3

Azerbaijan imports natural gas from both Russia and Turkmenistan to manage its domestic supply-demand balance. In November 2022, Azerbaijan signed an agreement with Gazprom, Russia’s state-owned gas producer, to import up to one billion cubic meters (bcm) of Russian gas through March 2023. The Hajigabul-Shirvanovka-Mozdok pipeline, which facilitates these imports, has an actual transmission capacity of approximately 5 bcm, making it a more practical option for addressing shortfalls in domestic supply. Turkmen gas is imported via swap arrangements involving Iran, but the Hajıgabul-Astara-Abadan pipeline — used for this purpose — has a significantly lower operational capacity of just 2.5 bcm, limiting its ability to offset Azerbaijan’s growing export commitments. Thus, it is the import of Russian natural gas to Azerbaijan that raises significant concerns in the context of Azerbaijan’s energy deals with the EU.

Crucially, neither the Mozdok– Hajigabul pipeline from Russia nor the Abadan–Hajıgabul pipeline from Iran is integrated with the Sangachal terminal or the SGC infrastructure, which primarily transports gas from the Shah Deniz field to European markets. This structural separation suggests that imported Russian and Turkmen gas is designated solely for domestic consumption. However, the presence of indirect swap and re-export mechanisms — particularly through Georgia and Türkiye — raises credible concerns about the potential for Russian gas to be “rebranded” as Azerbaijani before entering European markets. Such practices blur the lines of energy provenance, complicating the EU’s efforts to fully disengage from Russian fossil fuels.

The absence of stricter import controls on gas transmitted from Azerbaijan to Europe via the Türkiye–Bulgaria interconnector, coupled with the lack of isotopic tracing at Türkiye’s export hubs — where SCADA systems prioritize flow efficiency over origin verification — has enabled Ankara to bypass EU sanctions tracing mechanisms. These practices have heightened distrust in Brussels, particularly as the REPowerEU plan aims for a complete phase-out of Russian hydrocarbons by 2027.

Russia’s Energy Interests in Azerbaijan

This dynamic unfolds against the backdrop of increasing cooperation between Russian and Azerbaijani energy interests. Russia’s Lukoil — a major private oil and gas firm with close ties to the Kremlin — holds a 19.99% stake in the Shah Deniz gas field, Azerbaijan’s flagship energy project and the cornerstone of the EU-bound Southern Gas Corridor (SGC). Lukoil is also involved in multiple segments of Azerbaijan’s gas value chain, including the Shallow Water Absheron Peninsula (SWAP) exploration project, the South Caucasus Pipeline, and the Azerbaijan Gas Supply Company.4 Through these stakes, Lukoil stands to gain an estimated US$ 7 billion in profits over the next decade from gas exports that, on the surface, appear to be purely Azerbaijani.

Such developments raise critical questions about the extent to which the European Union has genuinely disentangled itself from Russian energy. Although Brussels signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Baku in 2022 — aiming to increase Azerbaijani gas exports to the EU to 20 billion cubic meters by 2027 — the path to meeting this target is far from straightforward. Azerbaijan faces structural constraints in rapidly scaling up production and export capacity. In response, Baku appears to be adopting a pragmatic strategy: importing Russian gas to satisfy domestic consumption, thereby freeing up more of its own production for export to Europe. This approach enables Azerbaijan to position itself as a “reliable” energy partner to the EU, even as it maintains discreet energy ties with Moscow.

One potential workaround involves shifting Azerbaijani gas exports from Georgia to Europe, replacing them with Russian imports into Georgia. SOCAR exports approximately 1.3 bcm of gas annually to Georgia via the Hajigabul–Gazakh–Saguramo pipeline. Azerbaijani gas also goes to Georgia from the Shah Deniz field via the South Caucasus Pipeline (Baku-Tbilisi-Erzurum). If Georgia resumes importing Russian gas, Azerbaijani gas currently sold to Georgia could be rerouted to Europe via Türkiye and Bulgaria using the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) and associated interconnectors.

Input-Output Imbalances of Azerbaijan gas industry

The strategic partnership between Gazprom, Lukoil and SOCAR has significantly enhanced opportunities for Russian oil and gas to reach European markets through Azerbaijan, while also presenting new avenues for Russian oil companies to participate in regional energy projects. These collaborations position Russian firms to benefit from increased access to Europe, leveraging Azerbaijan’s and Türkiye’s oil and gas infrastructure belongs SOCAR.

“According to Alexey Gromov of the Russian Institute of Energy and Finance, Azerbaijan benefited from the arrangement by purchasing 1.53 million tons of Russian Urals crude for domestic use in 2024, while continuing to export its own higher-value Azeri Light oil.”

Let us examine four potential channels through which Russian gas and oil could be rebranded and delivered to European markets under the Azerbaijani label.

A detailed arithmetic analysis of Azerbaijan’s natural gas input-output balance in 2023 offers revealing insights into the potential export of Russian gas under an Azerbaijani label. Here are the key figures:

- Total commodity gas production: 36.414 bcm

- Domestic consumption: 13.439 bcm

- Total natural gas exports: 26.623 bcm (State Customs Committee data)

- Total natural gas imports: 2.322 bcm (including 1.517 bcm from Turkmenistan, 800,665 mcm from Russia and 1,031 mcm from Kazakhstan – State Customs Committee data)

Input-Output Balance for Natural Gas:

- Input: Total production + Total imports

36.414 billion m³ + 2.322 billion m³ = 38.736 billion m³ - Output: Total exports + Domestic consumption

26.623 billion m³ + 13.439 billion m³ = 40.062 billion m³

Imbalance: The calculated input falls short of the output by approximately 1.326 billion m³ (40.0 billion m³ – 38.736 billion m³), raising questions about the source of the surplus gas attributed to Azerbaijan. This discrepancy suggests the possibility of Russian gas being exported under the Azerbaijani label.

Conclusion

Azerbaijan is unlikely to meet its pledge to supply 20 bcm of gas annually to Europe by 2027 due to production limits and infrastructure constraints. A more realistic export figure is closer to 14 bcm. This shortfall, alongside growing energy ties between Baku and Moscow, raises critical concerns about the potential re-export of Russian gas to Europe under the Azerbaijani label.

The arithmetic imbalance between Azerbaijan’s gas input and output — combined with opaque swap deals and limited EU oversight — adds weight to these concerns. Despite this, Azerbaijan continues to push for EU investment in pipeline expansion, but skepticism in Brussels remains strong. The EU sees Azerbaijan as a short-term stopgap, not a long-term strategic partner.

Complicating matters further is Russia’s deepening role in Azerbaijan’s gas sector, particularly through Lukoil’s almost 20% stake in the Shah Deniz field. That Lukoil remains unsanctioned in this venture highlights a glaring loophole in the EU’s efforts to sever Russian energy ties.

Ultimately, Europe must confront the contradiction at the heart of its energy strategy: a push to cut dependence on Russian gas while enabling its indirect return through Azerbaijani routes. Without tighter oversight and clearer supply chain transparency, these contradictions risk undermining the EU’s energy and geopolitical goals.

- Ibadoghlu, Gubad (2024), “Current State of Azerbaijan’s Gas & Oil Cooperation with Europe: Opportunities and Challenges.” Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4931082 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4931082 ↩︎

- Zero Carbon Analytics (2024) Existing gas supplies to meet EU demand under 2040 emissions target, Briefing 16 Jun 24 ↩︎

- Ibadoghlu, Gubad (2024): “Russia’s Energy Interests in Azerbaijan: A Retrospective Analysis and Prospective View,” SSRN, Rochester, NY, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4943332 ↩︎

- Ibadoghlu, Gubad (2024): “Russia’s Energy Interests in Azerbaijan: A Retrospective Analysis and Prospective View,” SSRN, Rochester, NY, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4943332 ↩︎